Text and Photographs by Stefan Heijdendael

"All you need to take the most beautiful pictures in the world is a simple Praktika with a 50 mm lens.

Stop wasting your time talking cameras, and go take pictures!"

— Hans Vree

________________________________________________________

In the Hague, the city in the Netherlands where I studied, is a special store. From the outside you see broken windows held together with plastic and tape, while on the inside you will find yourself in a photographers paradise. All kinds of cameras, darkroom equipment, and boxes with enlargement paper are everywhere. In the centre of the dimly lit store is a counter. And behind that counter sits Hans. He’s the kind of man you don’t want to mess with. He’s big, has a red beard, a loud voice, a razorblade sharp tongue and in a way he makes you feel you’re dealing with an authentic Viking instead of a shop owner. And of course, he is no ordinary shopkeeper. He is a teacher, a teacher of photography, for those aspiring to become good photographers. He is an ex-war-photographer, worked as a forensic specialist in photography, and for reasons I still cannot grasp chose to begin a shop to teach people how to master the craft photography. All the pros in the city come to him for technical advice. You’ll never get accepted as an official student, you’ll never pay any fees, and you can be sure that if he accepts you as a talented would-be photographer, he’ll shout and grumble at you for every mistake you make. And I’ve been shouted at a lot, I can assure you.

When I entered his shop for the first time my goal was clear. I wanted to become a photographer, and a damn good one. I had practiced with a simple Praktica, which I upgraded to a Nikon F601, with multi-pattern metering, a built in motor drive, and two zoom lenses covering a range from 35 to 200 mm range. I was proud of my equipment. But Hans was not impressed.

“Do you know what you are measuring when you meter a scene?” I sought the words to explain what I thought I was doing, but I could not answer the question, except for the obvious answers found in handbooks of photography. Hans went on: “You own two zoom lenses, but can you tell me what the characteristics are of a 35 mm lens? Or of a 200 mm? Do you know how a 50 mm draws the picture? Let me guess”, said Hans, “you use the zoom for framing, don’t you?”. I had to admit I was. He pushed further: “Did you ever

calculate the depth of field when taking a shot?” I had no idea what he was talking about.

It took half a year before I dared to show him some of my pictures. And I was criticized fiercely for what I had to show. He noted several major flaws in the technique of my pictures. Because of wrong metering the grain had become more poignant in my pictures. Dark areas showed little detail. Images were blurred because of the lack of a fast lens, and I used the wrong lens for the perspective I wanted. “But what gear are you using?” I asked him in despair. He exclaimed: “Why do you people always think it is the camera that takes the pictures? All you need to take the most beautiful pictures in the world is a simple Praktika with a 50 mm. And your eyes. Stop wasting your time talking cameras, and go take pictures!”

I sold all my Nikon gear, and bought a second-hand Canon F1, with a 50 mm lens. It is a difficult camera, because it is merciless. One mistake, and you are doomed. If you don’t know what you’re doing, it is a horrible camera. I did not know what I was doing. I was used to letting the camera do the thinking for me, and was punished with results that did not satisfy me. With the Canon, there was nothing there to relieve my mind when taking a picture, no automatics of whatever kind to help me out: Just film, a light meter, a shutter, a diaphragm and a lens. A basic camera. But less turned out to be more. For a basic camera gives you the possibility to experience the basics of photography. Which shutter time do you use? When can you still get a sharp picture? When do you use which lens to get the picture you have in mind? How do you handle extreme lighting situations? And in the end: How do you get the picture you want? With the help of Hans I gradually mastered the camera, and it did not feel as a camera anymore, but as an extension of my eyes. This simple camera trained my mind in a way that made it a tool for fast, swift, intuitive working; with experience and knowledge of how to take the picture I had in my mind. I also started to go to the library and got all the books of the great masters, which I studied. The masters of photography could do without multipattern metering and zoom lenses. They could have made their pictures with a Praktica. It is the eye that takes the picture. And the camera is an extension of the eye.

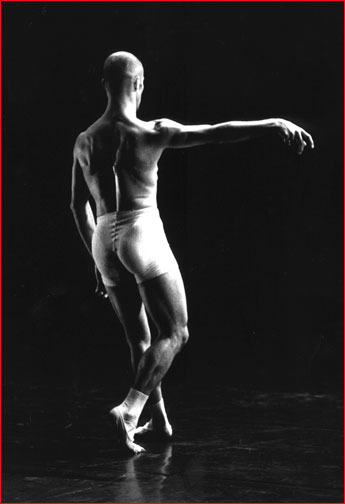

After five years of doing all kinds of photo work, and specializing in theater photography, I started working as a research journalist. I stopped working as a professional photographer. Around that time, digital cameras with resolutions of 3 MP made their way into the market. I never was too much interested in digital photography because of the lack of quality, at least in my view, and the high prices that had to be paid for a quality that did not equal film. And I was horrified by the prosumer cams thrown on the market with unacceptable shutter lag, slow auto focus (or, rather, the absence of a good manual focus possibility) and slow cycle times. But I also did not like them because of the inability to control them. Look for the basics on a digital camera. Most of the time, they are hard to find, hidden in menus. In the digital world at that time, a basic digital camera was not needed, nor wanted, except for the professional SLRs. It is great to see some traditional companies finally starting to build digital ‘basic’ cameras, like the Epson/Cosina digital rangefinder, and the Leica Digilux 2. In the end, I bought a 4 MP prosumer camera that had an acceptable shutter lag for shooting around the house. It is a nice cam for fun work,

but I would never dream of using it on an assignment. Since then a lot of good cameras have come out. And by now I’m convinced digital is as good as chemical photography. With a big assignment on the horizon, I’m even considering digital for my pro-work.

In the digital arena, I’m a novice. I do not have tons of experience with MP, dpi, noise, and moire effects. And when I look at the forums on the Internet a lot of people are sharing their experiences and knowledge to help each other make better pictures. I have a lot to learn: even though the end result of digital photography is the same as with chemical photography, the route to follow is completely different, and to me, far more technical than before. And that may confuse people, as I was once confused. I see a lot of beginning photographers ask questions that are very similar to mine, when I started out as a photographer. They are overwhelmed by tech-sheets, and by the possibilities of digital cameras. Digital cameras nowadays resemble computers more than anything. They have all the features you may like, they can be tweaked infinitely, and they are more flexible than ever before. Is that an advantage? Yes, it is, if you know what you’re doing. If you know how the combination of a shutter, a lens, a diaphragm, and a light meter can make a picture. And I can say this safely because I made the same mistakes: A lot of people do not know the basics, and thus, will never be able to get the results they want.

If you consider a picture as a frozen moment in time, captured on a light sensitive medium, it is easy to see that the end result of your finger pressing the shutter had its origin in that unique moment. Can you alter that moment? Yes and no. Yes, you can tweak the image in a darkroom or in Photoshop. From a RAW image, it is a good thing you can adjust metering failures. It is great you can tweak sharpness, contrast, color, and noise. It can bring one great results. But it can also get you into serious trouble. Because if you disregard the quality of the frozen time-moment, there is no way you can make up for that. If a negative, or a RAW file is no good, you can make it acceptable, maybe good, but never perfect. But more importantly: you can never capture THAT moment again. It is the base to be used to get the desired end result, and thus, very important. So is it a good thing you can fire away with a digital camera without end? Is it a good thing the camera handles the basics, giving you the possibility to concentrate on the picture, as camera adds often state? Yes. But only if you mastered them first.

Last week I went to Hans again in his photo store. He was a bit moody. “You know what”, he said while drinking his espresso, “a lot of people see digital as a religion. With digital you can do this, you can do that, you can do everything. But nothing has changed! You still press the shutter, and still the end result is a photo. But because it is labeled digital, people think photography is easy. Starting photographers look at themselves as picture builders, instead of picture takers!” I could not have agreed more.

So here’s some free advice from a novice in the digital arena to novices in the field of photography. And of course it is Hans who brought me to this advice. Restrict yourself. Forget about tweaking, and try to get the most perfect frozen moment in time, which will serve as a good base for a print. How? If you don’t want to spend a lot of money, go to a second hand photo store and go look for a basic single lens reflex. There are thousands for sale, and they cost little. Like a Minolta SRT101, Canon Ftb, Nikon FM, Olympus OM1 or maybe, if you’re on a really tight budget, a Praktica. Buy ten rolls of slide film and start to take pictures. Experience failure. Curse yourself when you miscalculate. Choose the wrong parameters. There are only a few rings and dials to master on these basic cameras. You can do that! And when the camera has become your third eye, an intuitive extension of your brain, go to the library and study the work of the great masters. Look at all these beautiful slices of frozen time. And than take your digital camera and put in practice what you learned. You’ll be a better photographer. And you don’t have to take my word for it. Take Hans’.

© 2004 — Stefan Heijdendael

________________________________________________________

Stefan Heijdendael(b-1974) worked as a professional photographer between 1994 and 1999 in the Netherlands. He specialized in theatre and dance. His pictures were published in several magazines, newspapers and printed postcards. He now works as a research journalist for Dutch public radio.

________________________________________________________

You May Also Enjoy...

PHOTOGRAPHY, RAIN OR SHINE

"Waterfall on Rock"ALPA 12 SWA with Rodenstock 180 mm APO HR lensINTRODUCTION I recently traveled to Iceland to teach at a workshop organized by PhaseOne

Submissions Page

‚ This page is inactive‚ Submissions Have you climbed to the top of the mountain? Do you have images that you wish to share with