This is a description of what some might regard as a fool’s task – to put together the highest quality digital image capture system that today’s technology provides. The process required making decisions about several major components, including the camera platform, digital back, and the lenses to be used.

Though by no means inexpensive – the total system put together here costs about the same as a high-end new car – pros at least can lease as well as write off or depreciate their investment. Whether this particular photographic system would be one that suits anyone’s needs other than mine is not for me to say. Each of us has to decide for ourselves what our particular needs and uses may be.

_________________________________________________________________________

Linhof M 679cs

There are two things you have to know about me. Firstly, I’m compulsive about image quality. Secondly, I’m inconsistent. For example, I’ll take getting the shot with whatever gear is needed, over not getting the shot at all, because it would have meant a compromise on image quality. The shot always comes first.

On the other hand, if I’m going to get up at 3 am, drive for 2 hours, then hike in the dark for an hour with a 35lb camera backpack so as to be at the right spot for light as the day breaks, I want to have the best equipment possible. If I’m going to spends thousands, or even tens of thousands traveling to some remote part of the world on a landscape shoot, I damn well insist on the finest image quality possible.

Like I said, I’m inconsistent.

In the 40 some years that I’ve been doing photography I have shot all formats, from sub-35mm to large format. As a photojournalist I worked mostly with 35mm, but I also used medium format for editorial, and large format for advertising, architecture, and my own personal fine-art work.Horses for courses, as the British say.

Over the past 5 years or so, as I transitioned completely to digital, thesize equationhas become murkier. In the days of film it was a truism that the bigger the negative the higher the image quality. 4X5" trumped medium format, and medium format trumped 35mm. No one with any real-world experience debated this. But convenience, shooting speed, media costs, and bulk, were all variables that had to be considered, and compromises made.

The low noise and clean images provided by digital was compelling, even if in the early days sensor size wasn’t large enough to compete with film. But, once we got beyond 6-8 Megapixels this changed. This as enough for full page magazine reproduction or an A3 sized print. Once we got to 11MP we were able to produce double page spreads and quality 13X19" prints, and by 16MP (where we are now in 135 format) we were not only surpassing 35mm film, but actually equaling medium format. (I know that some holdouts find it hard to accept this, but these are typically people that haven’t discovered this first hand for themselves. Professional photographers by the tens of thousand have, so the debate is no longer of much interest).

That left compulsives like me with the question –where do we go for even higher quality? The answer of course was medium format backs. I took this route, first with a 16MPKodak DCS Probackand then aPhase One P25, both on aContax 645system with Zeiss lenses.

But after more than a year of shooting both with a 16MPCanon 1Ds MKIIanda 22 MPP25back on the Contax, I came to a couple of realizations. The Canon and Zeiss lenses on their respective cameras were not the equal of their sensors. In other words, the sensors were outperforming the lenses. Even using the best primes on the Canon proved to me that the 1Ds MKII was not being pushed to its limit, and using lesser lenses often disappointed.

On the Contax with its Zeiss lenses, I believed that there was a match with the P25 back. But this opinion was to subsequently change. But before describing this epiphany, which took place in late 2005, I need to make one additional observation, if not an actual confession. That is – in prints up to 13X19" I often did not see significant real world differences between work done with the 1Ds MKII using my best Canon lenses, and the Contax with P25 and Zeiss lenses. Yes, I know that the P25 is true 16 bit, yes I know that the photosites are larger, yes and know all the other theoretical advantages. What I’m describing is not theory, it’s practice.

The gizmo attached to the rear standard’s accessory shoe, with a WhiBal black card attached,

is used as a third arm to shield the lens from flare. It’s called a FlareBuster.

But the operative phrase here is "best Canon lenses", because with the Zeiss primes on the Contax compared with almost all the Canon zooms (which I mostly use for convenience sake) it was the opposite story.

All of this produced the following summary. Most of the time the Contax/Zeiss/Phase One system outperformed the Canon system. Not by a huge amount, but noticeable, except when the best lenses and best technique were used with the Canon (heavy tripod, mirror lock up, optimum aperture, prime lenses), in which case the visible differences on prints up to the resolving power of each system were not that significant in comparison with the P25.

Then came the epiphany. I was loaned aCambo Wide DSbody with a35mm Schneider Digitarlens for with use with the P25 back. This was an eye opener. The image quality, in terms of resolution, detail, contrast, "transparency", and microdetail was so dramatically better than anything that I had ever produced with the same P25 back on the Contax with Zeiss lenses that I was drawn to only one conclusion – once again, as with high-end 35mm digital, the sensor was being let down by the lenses.

I started making some phone calls and writing some emails to the handful of photographers who I knew were working with Schneider and Rodenstock "digital" lenses on medium format view camera systems – asking if they were seeing what I was seeing, and I was told universally –Sure. Didn’t you know this?

No!No, I didn’t. But what I learned from them and from further discussions with knowledgeable people in the industry, is that about 4-5 years ago both companies set out to design a series of lenses specifically for use with digital backs. But, rather than design them for Hasselblad, Contax, and Mamiya lens mounts, they were designed to be used on technical view cameras. This made them "universal", and also recognized that the photographers that would likely be using them would have the need for technical movements, whether this was for product, advertising, or architectural work. Consequently, in additional to superlative resolution these lenses were designed to have large image circles so that movements on technical cameras would be possible.

_________________________________________________________________________

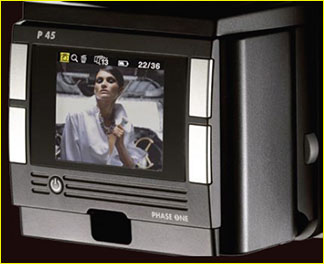

The P45 Decision

On top of this revelation (today’s sensors are being held back by yesterday’s lenses) came the release in early 2006 of thePhase One P45. This was the first medium format back to ship with the new 39 Megapixel Kodak CCD chip – the largest and highest resolution single shot back and sensor commercially available.

So, as a compulsive neurotic when it comes to image quality, I could only imagine what one of those high-end digital-specific lenses in combination with a P45 would be like. Putting the P45 on my Contax/ Zeiss system would, of course, produce larger files than those from the P25, making bigger prints possible as well as the ability to crop when necessary and still have a large, usable file. But, since the weak link in the chain was clearly the lenses on my Contax (remarkably), would it make sense to spend the money for an upgrade to the P45 for file size alone?

My decision was that it wouldn’t, and when combined with the knowledge that Contax has almost certainly now gone from the scene, for that big dirt nap in the sky (read – they ain’t coming back), I knew that my next upgrade path was to a technical view camera.

This would offer several advantages. Firstly, it could use any of the new ultra-high resolution lenses from any manufacturer. All that’s needed is a lens board. Also, the ability to have movements available (more than theCambo Wide DS‘ simple rise and shift) would be a big boon on a major multi-year architectural commission that I’m engaged in. Thirdly, having sold my Contax gear, I would be free when upgrading from the P25 to the P45 to switch mounts. I therefore decided to switch to theHasselblad Hmount. This would allow me to test other new backs as they come along, because the H back has now become the new standard, with Hasselblad’s H2 becoming one of the few remaining medium format system. Previously, backs in Contax mount were always hard to get ones hands on, as they were never the first to be released, and also were usually not available from manufacturers and dealers as evaluation units.

Finally, if I did want to ever test or use another brand-mount back, a simple change of the rear mounting plate on the view camera would allow this. Maximum flexibility. Compelling logic.

To answer the question that someone is bound to ask –why didn’t I consider theImacon39MP back– the answer is simply that because I owned a P25 I was able to get a very attractive trade-up to the P45 fromVistek, myPhase Onedealer. Also, at the time of this transaction, late February 2006, the Imacon backs are still not shipping (though some dealers have samples available). Finally, I am familiar and comfortable with Phase One products, including theirCapture Onesoftware, and find them to be reliable for field use and very well designed and built. Image quality has also been nothing short of exceptional.

_________________________________________________________________________

Why the Linhof M679cs?

Image Courtesy Anagramm

The next question was – which view camera?

There are at least a half dozen "small" view cameras on the market, including those fromArca, Cambo, LinhofandRollei, the four that I considered. In the end I chose theLinhof 679csbased on a combination of features, weight, bulk, build quality and price. One of the things that I particularly liked was that it comes with a base platform featuring comprehensive adjustments that obviated the need for the added weight and cost of a separate ballhead, leveling base, or something like theArca Cube. The name of the game in view camera use is precision positioning, and a simple ballhead is too coarse a device when camera movements are involved. The Arca F Line camera is lighter than the Linhof, but when you add the size, weight and cost of the Arca Cube, that equation changes.

It needs to be added that this isnot your father’s 4X5 view camera. The 6X9 format technical cameras introduced over the past 5-8 years were originally designed for use with film, with 6X9cm as the largest common size when using 120 or 220 roll film. But medium format backs with their roughly 645 format and similarly sized sensors are a perfect match, and many of these cameras have subsequently been reengineered for more appropriate use with digital backs rather than roll film holders. And, while it’s unlikely that we’ll see sensors larger than 645, if they do come along then these cameras will be able to handle them. In other words, a 6X9 camera offers a high degree of obsolescence protection while high-end digital photography continues its evolution.

At 3.8Kg (8.4 lbs) the Linhof is no lightweight, but remarkably not that much heavier and bulkier than a complete medium format system when it comes to backpacking it to location. (That no tripod head is needed with the particular model also needs to be factored into any weight comparison). Of course the setup and shooting with the technical camera is slower that a medium format SLR, but then if I want speed I can and do use theCanon 1Ds MKII.

Compared to the weight and bulk of a 4X5" view camera, especially a monorail, the choice of a 679 was an easy one to make. I don’t expect to ever shoot sheet film again, so I lost little to nothing in downscaling the camera itself, and gained a lot, particularly in terms of bulk, which counts for me more then weight in many situations – especially when traveling and working on location.

Rounding out the Linhof system for use with a digital back one needs a sliding adaptor. This allows for rapid switching between a ground glass with hood or viewer, and the digital back. I chose the Linhof brand version as it offers appropriate features, including stitching capability (more on this below). The Linhof sliding back allows one to focus and compose with the usual ground glass, hood and viewing aids. I chose it rather than one of the third party devices, again because of fit and features. To switch between the ground glass and back one simply presses a lever and the back slides into precise position. Takes just a second and is very secure and accurate.

A final selling point was that Linhof has designed the 679 so as to specifically accommodate the use of digital backs. The early Lightphase and similar tethered backs, with their weight and cable drag, made this design consideration a necessity. The latest generation of backs which are self contained are smaller and lighter, but compared to a sheet film holder, these are still heavy. The 679’s design therefore takes this into account.

I decided not to go with a right angle viewer. These are useful in that they provide a right-side up (though laterally reversed) image. The problem though is that they force the camera to be used as much as a foot lower, since one is looking downward. So in the end I went with a simple groundglass surrounded by a compendium bellows with a 4X magnifier. This works well and makes a dark cloth unnecessary (though I still carry one for use in ultra-bright conditions such as when working in snow). The Linhof system also includes a movable fresnel lens inserted into the groundglass holder. This is a critical piece, since it allows the bright spot of the image to be moved for focusing purposes when lens movements are used, and with the very wide 35mm lens – otherwise the image can effectively disappear, especially in the corners.

This all means that the groundglass image, as with all view cameras, is upside down and backwards. Anyone who uses view cameras regularly will quickly become used to this. And, as I learned years ago when teaching view camera technique, it helps people "abstract" the image. In other words, it forces you to consider the image asdesign, rather that focus on its literal content. In other words –composition above content. The content is there because you chose to take the shot. You can see it with the unaided eye. On the groundglass ones attention becomes focused on framing, DOF, exposure and technical movements, and for these looking at an upside down and laterally reversed image can actually be an aid to composition, not a hindrance.

_________________________________________________________________________

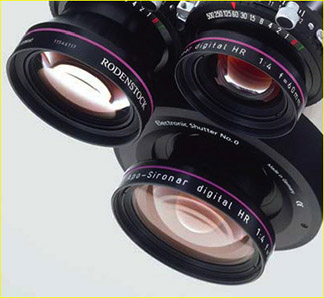

Rodenstock HR lenses

The lens brand decision came down to –SchneiderorRodenstock. It was a tough call between them as they are two of the most venerable yet innovative lens makers in the world. But in the end I went with Rodenstock for two reasons. The first is that I wanted a 35mm focal length lens (equivalent to about a 21mm in this format), in 135 terms). The Schneider Digitar 35mm will not focus to infinity on a view camera with a sliding adapter. It will on something like the Cambo Wide DS, where it is in a helical mount and can be positioned just millimeters away from the chip plane. But on a camera like the Linhof, even with the wide angle bellows in placeanda triple recessed lens board, it won’t work.

TheRodenstock HR 35mm f/5 Apo-Sironarwill, as it is a retrofocus design. This also means that light hitting the sensor from the lens’ edges is arriving at a less acute angle, reducing vignetting and colour shifts. (Whereas retrofocus wide angle lenses are sometimes not that well regarded, this new design turns that assumption on its head.)

The decision to obtain this lens made me look at theHRline in general. (More on what HR means in a moment). There are only now 5 HR lenses in the Rodenstock line-up – a 28mm, 35mm, 60mm, 100mm and a 180mm. The 28mm is too wide for my needs. I’ve gone for the 35, 100 and 180, skipping the 60, but instead purchased a non-HR lens of that medium-wide focal length, theApo-Sironar digital 55mm f/4.5. Why? In a word –coverage. And this also helps explain what the HR lenses are all about – the good news and the bad. (NB:The 28mm and 180mm are brand new as of March, 2006 and may not yet be listed by dealers or mentioned on any web sites. Be assured that they do indeed exist and can be ordered).

Rodenstock’s’ and Schneider’s line of digital view camera lenses have relatively large image circles. The 55mm Apo Sironar’s, for example, provides a 150mm diagonal at f/8. This is more than enough for all the movements one could want on an imaging chip with a 61mm diagonal.

But the HR lens line’s abilities go beyond even the extreme high definition of Rodenstock’s other excellent optics, providing resolution comparable to that of the finest prime 35mm format lenses. (Most people know that large format lenses typically have lower resolution than those for medium format, and those for medium format lower that for 35mm. The reason being that they don’t need to have high resolution because they will not be enlarged as much. But this rule of thumb from the days of film now needs to be left behind us).

HR lenses are actually specified by Rodenstock as surpassing the resolution capabilities of digital sensors with pixel dimensions down to 5 microns. The P45’s pixels are 6.8 microns square, so these lenses should be able to support even any subsequent generation of backs. (A 645 format sensor with 5 micron pixels would have between 55-60 Megapixels, and according to Kodak’s chip designers is do-able. Whether anyone needs this, or any back maker will make one, remains an open question. I wouldn’t expect to see such a back, if at all, for at least another two years).

To achieve resolution that is at the extremes of what current technology can produce (outside of NASA that is, and without their budget),Rodenstock had to design these lenses with a smaller image circle – 70mm. Thisjustcovers the diagonal of a back like the P45, with its 36.8 X 49.1 mm sensor. The diagonal is 61.3mm, which means that one only has a small amount of ability to rise or shift the lens. Sometimes this 5-10mm is all that’s needed, but in really it isn’t much for some applications.

The good news is that while these lenses have restricted ability with regard to rise or shift, these movements aren’t used as much when doing landscape work as are tilt and swing. And by tilting or swinging the rear standard rather than the lens standard, very little if any increase in lens coverage is required. So the Scheimpflug effect is quite usable with HR lenses, offering extended planes of focus. (Rear tilt or swing does, of course, produce some perspective alteration, which such movements do not when done on the front standard. But for landscape work this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because it tends to favorably exaggerate near-far object relationships).

Being able to use Scheimpflug with the HR lenses can be important, because these lens should be used stopped down to no more than to f/8 to avoid reducing resolution due to diffraction effects. (In a rarity among camera lenses, the HRs truly are diffraction limited). The 35mm and 100mm HRs are f/4 lenses, and their optimum apertures are f/5.6, with f/8 still being close to optimum. Beyond f/11 resolution has visibly started to deteriorate, though it is still very high by normal standards.

Machine Art, Toronto – March, 2006

Linhof 679cs with 100mm Rodenstock Apo Sironar HR and Phase One P45 back

View camera users of larger formats are used to stopping down considerably more than this. But, it needs to be borne in mind that with the small imager size used, vs 4X5" for example, comparable depth of field is attained at much wider apertures.

Other areas in which lenses like these differ from lenses made for film use is that they take into account the 2mm thickness of the back’s coverglass / IR filter, reduced image size, and greater focal plan flatness. These are also true Apochromats, a necessity to avoid chromatic aberration (fringing).

Finally, the reason I went with the regular (non HR) lens at the 55mm focal length is so that when extreme movementsareneeded, I would have at least one lens that would provide that ability. At 55mm, which is medium wide-angle in this format, it’s probably as close to ideal for architectural work as one would like. So, I believe that this four lens outfit – very wide, medium wide, slightly longer than normal, and short tele, will likely do most of what I need for landscape and architectural work.

One more thought on the issue of camera movements. Some people say –why bother with rise and fall (or shift), when Photoshop provides perspective control capability? This works to some extent, but because it uses interpolation to create new data, image quality suffers, and the perspective produced is usually somewhat distorted. In my experience, simply not good enough for demanding fine art or commercial work, especially commercial architectural assignments.

_________________________________________________________________________

Shutter Type

I seriously considered ordering the lenses withRolleielectronic shutters. This would have also, of course, required a Rollei hand controller unit. The considerable advantage of such a system is that no cocking of the shutter is needed, and also setting the aperture, shutter speed, and opening and closing the preview lever are all done from the controller, meaning there is no need to move back and forth between the front and the back of the camera.

The considerable extra cost was definitely an issue, but I was also deterred by the added complexity, cables, and need for another battery and charger. Some testing showed that I wasn’t going to be happy with the extra components, bulk and complexity. For studio work it would be ideal, but not for use outdoors, when hiking, and in inclement weather. So i put up withcock the shutter, open the aperture, set to preview, close the aperture, reset preview, and then do it all over again for the next shot.

_________________________________________________________________________

Kish Mini Director’s Viewfinder

Photographer’s use a lot of gizmos and gadgets. One that is standard equipment for many film directors, cinematographers, and videographers is aDirector’s Viewfinder. This is typically not something that still photographers use, because to frame up a shot one simply puts the camera to ones eye. But film makers with their bulky equipment, and directors who don’t spend their time behind the camera, need to be able to pre-visualize the shot. Asking the camera crew to set up a large film or video camera in a specific spot so that the DOP (Director of Photography) or the film’s Director can decide on exact positioning and lens choice simply isn’t practical. Consequently there are devices calledDirector’s Viewfinders, which typically hang around the DOP’s neck, and which are used to previsualize the shot and choose the focal length needed.

But anyone using a view camera faces the same issues. These aren’t carried around one’s neck or over the shoulder, readily available to frame the shot. They also don’t use zoom lenses or have viewfinders, and so even if you’re walking around a potential scene with the camera on a tripod, setting up the shot with the right positioning and focal length choice can be tedious.

For this reason, when working with a view camera I have always enjoyed using a Director’s Viewfinder. Simply set the device to the aspect ratio of the film or sensor being used – 1.33 for medium format digital, and then zoom the viewfinder to the focal length needed. Or set the focal length of the most suitable lens available and the find a spot to position the camera that frames best. Then it’s simply a matter of unpacking the camera and the appropriate lens right in the spot that you’re going to shoot from.

There are about a half dozen different such devices available from companies that provide supplies and services to motion picture and TV production crews. The one that I ordered is theKish Optics Mini Viewfinder. It retails for about $300. Not the greatest, but the price is right.

_________________________________________________________________________

Why Not a Scanning Back?

Anyone searching for ultimate image quality has to consider the use of a scanning back such as theBetterlight. With resolution up to 12,000 X 15,900 (1.1 GB files) these surpass single shot backs using the new Kodak 39 Megapixel sensor (225MB). I have seen the work ofSteve Johnson(wall-sized prints with jaw-dropping quality), and I have also watched him work with his Betterlight (myAntarctic Workshopin December, 2005), on which Steve was an instructor.

As remarkable as images from such backs are, the don’t suit my working style. They require the use of a tethered laptop computer in the field (increasing complexity and gear by a factor of at least 2X), and exposures can run up to a couple of minutes in length, negating their use for many shooting situations in which I regularly find myself.

But, since they are half the price of a state-of-the-art back such as the P45, they may be a viable alternative for some photographers, and offer even higher image quality, though with commensurately less shooting flexibility.

_________________________________________________________________________

Panoramic Stitching

I have had a long time love affair with wide format photography. I’ve owned and used aFuji 617andHasselblad Xpanamong others. But, I no longer shoot film, and the market is likely (almost certainly) too small for anyone to create a wide aspect ratio large format digital sensor or camera. Consequently, when the subject matter presents itself I’ll sometimes take overlapping frames and stitch them together. This works, but often not as well or as easily as one could wish.

With a digital back on a technical camera, and a sliding / stitching back like the one from Linhof, it is simple to create 2.2:1 aspect ratio images. With a P45 this means files that are 11,900 X 5,375 pixels. A file like this is capable of producing a print that’s 22 X 50 inches at 240 ppi.

The way that these are produced is simplicity itself. In addition to a center position into which the digital back normally slides when replacing the ground glass, there is a notch to the left and a notch to the right, which positions the back further to each side of the 90mm wide opening. You first take a frame with the back at the left side position and then the right, just re-cocking the shutter between frames. This takes no more than the second or two that it takes the back to write the file to the CF card.

ThoughCapture Onehas stitching software built-in, I don’t use it as I find that it never does a good job, becauase it is calibrated for the Phase One stiching back, not the Linhof’s. There’s a simple solution though. Simply process the two raw files using the same white balance, and then process them into Photoshop. Create a new file with a large enough canvas, and then copy the two files onto the new one. Each will be on its own Layer. Line them up to roughly overlap, and then enlarge the join area to about 300%. Reduce the transparency of one of the Layers to about 75% and then move them so that they are in registration. From a P45 back the final file will be about 366MB, so a computer with a fast processor and at least 2GB of RAM are a virtual necessity.

The reason why this system is so easy and perfect in its results is because you are actually taking two separate exposures of the same image though the same lens. Because technical view camera lenses cover a larger image circle than needed, you are in fact just using more of the available circle than one frame can capture by itself. This is why there is no distortion or registration problems.

I have found that all of my lenses with the exception of the 35mm Rodenstock HR have a big enough image circle to accomplish this without any vignetting, even with the back in the horizontal position, thus yielding a distortion free 2.2:1 aspect ratio image of stunning quality and extreeme enlargability.

_________________________________________________________________________

Film? What’s Film?

At my seminars and workshops, when someone asks me a film related question, my usual response is, "Film? What’s film?. Oh, ya, I remember. We used to use that in the last century, didn’t we?"

Sometimes this gets a laugh. and sometimes a glare, but it is only meant in jest. Indeed there is a place for film, even with the ultimate digital view camera. One of these uses is as backup. One doesn’t carry a spare digital back, and unless you are shooting in the heart of one of the world’s major cities that has a medium format back dealer, you’re going to be SOL. Even getting a next-dayFedexreplacement, whichPhase Onedoes for its premium support package customers, isn’t going to do much good if you’re in the middle of the Namibian desert.

The backup solution then is film. A 120 film back and a dozen rolls of film is all that’s need to prevent disaster on location. Most people will have fallback lenses, and a shutter can be swapped out for one from another lens. The body of a view camera is so simple that even a torn bellows can be fixed with gaffer tape. So the back is the single greatest point of vulnerability, and so film is the ideal backup for digital.

I also always have a film back along when shooting digital for those things that digital doesn’t do as well, such as very long exposure – those measured in hours, such as start trails, and for the time when all battery power fails. In the case of the Linhof, a used Hasselblad A12 magazine and a V series adaptor plate is all that’s needed to turn the 679cs into a (dare I utter the words)film camera.

Don’t leave home without it.

NB:My initial tests show that the P45 produces stellar (no pun intended) results even with exposures as long as 20 minutes, so it appears that multi-hour star trail photographs will one of the few types of images that this back won’t be able to handle.

_________________________________________________________________________

A Word of Thanks

Equipment like that described in this article isn’t put together casually. Not only because in aggregate it costs more than most people’s cars, but also because it is comprised of pieces from multiple manufacturers (Linhof, Phase One, Schneider) all of which have to be put together to work in concert. Therefore, while there are on-line stores which will put this together, shopping just for rock-bottom price regardless of source is not the best approach. You’ll save some money, to be sure, but in the end who do you turn to when things don’t quite work together the way that they should?

I was fortunate to work with people who know this equipment inside out, and who were able to put all the pieces together for me, so that I had the confidence that everything would work properly. My dealer wasVistek, in Toronto, Canada. They sellPhase One,LinhofandRodenstockproducts and so were able to act as a single source. The sales consultant who is head of theirDigital Capture Group,Joe Behar, was able to help me specify the components needed, avoiding some costly mistakes.

I’d also like to thankMichael BoylanofBlazes Photographic, who acted as an advisor to me when selecting certain components and configurations. His in-depth knowledge of the current medium format digital view camera environment, as well as technical acumen, is unsurpassed. (Incidentally, Blazes is the Canadian distributor forSilvestricamera products).

There are three cables needed, all joined together by a special device from the KaptureGroup.

A standard shutter release cable runs to the release socket on the lens’ shutter

and another to the PC flash connection on the lens. A third goes to the digital back.

This allows the back to synchronize with the shutter release, since otherwise, and unlike with

a medium format camera, there is no means of communication between the back and the lens.

_________________________________________________________________________

Suggested Reading

There is to my knowledge nothing in print or on the web about large or medium format view camera technique with digital backs. An essay on this site from last year titledDigital View Cameras in Use and on the GobyRalf Lange, is one of the few references available.

A view camera / digital resource you may find of use is theMedium Format Forum on Rob Galbraith.com. A number of the members there are pros using MF backs on their technical cameras. A search of the history files will turn up a number of interesting discussions.

There are no longer that many books in print on view camera technique. Two which I can recommend are Leslie Stroebel’sView Camera Technique, 7th edition. It was published in 1999, and has some references to digital backs, though they are quite dated by now. Unfortunately its description of how camera movements work is simply awful. Nevertheless the book is a goldmine of information for anyone new to technical camera use.

Jack Dykinga’sLarge Format Nature Photographyis more inspirational than instructional, but is also amust-havefor any view camera enthusiast’s library. If you want to understand the joy of large format nature photography, this isthebook to own.

_________________________________________________________________________

Why Not Film?

View cameras are, if anything, growing in popularity. While medium format in general shrinks, and digital SLRs have virtually replaced film-based cameras, LF sales continue to boom, with more brands and types of these cameras on the market than ever before.

There are likely several reasons for this.The main one, I believe, is that as mainstream digital photography has become commoditized, there are photographers who want to work in a simpler more direct manner – out of the mainstream. They also are after extremely high image quality, and find the rarified prices of top-of-the-line DSLRs to be prohibitive. After all, a modest film-based view camera system with 2-3 lenses can be put together for less than a few thousand dollars.

The use of movements will always remain attractive to many. While Canon has three tilt/shift lenses available, these are not the sharpest knives in the drawer, and for many applications do not offer sufficient movement. Also, Photoshop will never be able to do Scheimpflug.

So, why purchase a $20-$30,000 digital back rather than use film? Setting aside the price part of the equation for the moment, the answer is the same as can be made for high-end DSLRs. Digital image quality is superior to that of film. And when you factor in ease of use, speed and assuredness of results, and flexibility of image processing, there isn’t that much of a contest any more.

Then there’s the matter of price. With the view camera body and lenses being essentially the same price whether one is shooting film or digital (depending on accessories), it’s the cost of the back that is the prime factor. This is where the math will differ for each photographer. (Digital specific lenses are somewhat more expensive than film lenses though).

I have shoot roughly 2,000 frames a year with my medium format system over the past few years. In comparison with $5 / frame for film and processing with 4X5 sheet film, a $30,000 back will be amortized after 6,000 frames, which for me will represent 3 years of use.

But then there is the matter of scanning. (I have long left the chemical darkroom behind me, for all the obvious reasons, including image quality).

If I were to have drum scans done, figure on a minimum of $75 each. Even scanning just 5% of my images will cost $7,500 / year. Buying my own drum scanner (even a used one) is not something I have the physical room or patience for, and a desktop scanner with comparable quality, such as the Imacon 828, cost $15,000. If course then there’s also the considerable time involved in scanning and dust retouching.

Put it all together, and at the volume of shooting that I do I can’t affordnotto buy a $30,000 medium format back rather than shoot film.

As the saying goes,your mileage may vary. But for many working pros, and even fine art photographers with high productivity, the financial equation needs to be examined carefully, even in the absence of compelling operational advantages.

In The Field

Though a sliding back with medium format digital back attached is a lot bulkier than a simple film holder, a single 2GB Compactflash card can hold some sixty 39 Megapixel image files. (These open up to 224 Megabyte images in 16 bit mode in Photoshop). Sixty images would require 30 film holders, more bulk and weight than anyone would want to take in the field. Of course one can load and unload sheet film in a changing bag while on location, but that’s not my idea of a good time.

And another 2GB card holds another 60 shots. It’s as simple as that. The financial as well as practical equations were compelling for me and the type of work that I do. Others will need to do their own analysis.

_________________________________________________________________________

Caveat Photographer

If you have worked with 4X5", or any view camera before, then a system such as this will not seem that unfamiliar, either in terms of bulk or workflow. Using the sliding back holder to shift the digital back and ground glass back and forth will be new, but this becomes second nature pretty quickly. Otherwise the use of this system is not that dissimilar.

One thing that will become clear after the first day is that the system is relentlessly unforgiving of any flaws in set-up. The back and lenses draw such a detailed image that even the most minute error of focus, or slight mispositioning of one of the standards, will be glaringly evident when the 225MB file is later viewed on screen at 100% mangification. With large format sheet film errors such as film buckling and film holder mispositioning happen. With a digital view camera the potential errors are different, but no less devastating. Shooting with this system requires a level of attention and concentration unlike that found with almost any other type of photography.

_________________________________________________________________________

The End of History?

Is a setup like the one that I’ve put together in any way the end of the line? Likely not, though in some ways I believe that it will be a while until we will see anything markedly superior come along.

TheLinhof 679csis the culmination of literally a hundred years of camera design on the part of that company. The currentcsmodel is the third generation of this particular variant. Since view cameras are such basic devices, as long as you have rugged construction and an appropriate range of movements, combined with light enough weight for field use, it’s hard to imagine what could supercede it.

ThePhase One P45at 39 Megapixels has caused many working pros, as well as industry observers and pundits, to ask –do we really need more than this? Some have even asked –do we even needthis?

Far be it from me as a seeker after the "ultimate" to sayno, but I think that along with the slowdown in Megapixel growth seen recently in the digicam and DSLR markets, we will similarly see a pause for breath at the very high end. There may be a 50 – 60 MP back somewhere down the road, but I don’t expect to see it for at least another few years, if at all.

Finally, there’s the matter of lenses. With the currentSchneiderandRodenstockmedium format lenses designed for use with technical cameras with digital backs, and especially Rodenstock’sHRline, we have lenses that define the state of the art, and which are truly a match for the highest resolution sensors. So, with a balance of capability between sensors and lenses, we may, for a while at least, have reached an equilibrium that hasn’t come yet to the DSLR marketplace.

The end of history? No, naturally not. But maybe an intermission.

_________________________________________________________________________

So?

Having read this far, you likely want to know –So, was it worth it?

The answer is that as this is being written in early March I have only had the system together for two weeks. Because it’s late winter where I live, the opportunities to do any real field work locally are limited. Consequently all I have had time for is a couple of hundred test frames. Enough to become familiar with a new camera, four new lenses and a new back, but not much else.

But, in mid-March I will be doing a week-long shoot inRedwoods National Parkin Northern California, and along the central coast, and then beginning in early April a three week shoot inNamibiaandSouth Africa. These will obviously tell the tale, and after each one I anticipate publishing not only images but also field notes and conclusions. I will also be producing a test report on the P45 once I have enough real-world experience with it.

_________________________________________________________________________

A Final Thought (for now)

My experience has been that my P25 outperformed the Zeiss lenses on my Contax 645. With the question of whether or not to therefore upgraded to the P45 I was left with the question of whether such a step would be worthwhile, or would simply provide me with bigger files (an advantage in many instances to be sure).Mysolution was,don’t raise the bridge, lower the river. In other words, when moving to the P45 I decided to upgrade to a system with lenses that would be a performance match to the back.

The question is bound to be asked by others (and has been several times already) –if I currently own a Contax / Hasselblad / Mamiya or whatever, is a move to a 39 Megapixel back going to be worthwhile?

The only response that I can give is to point to the experience of two photographers who I know that have also purchased P45s in the past couple of months.Charles Cramerhas moved from some 30 years of shooting 4X5" film and doing drum scans, to working with a P45 and Mamiya 645 system, and reports that he decided to get the P45 based on some impressive tests comparing 4×5 with the digital back. He adds that while he is "optimistic" about the results, "I really don’t know how I’ll feel about my decision to change until I get some real work done…".Ditto.

Bill Atkinson, after upgrading from a P25, has reported to me that he has found that a P45 on hisHasselblad H1with itsHasselblad/Fuji macrolens is clearly showing comparable image resolution to that from hisBetterLight Super 6K-2scanning back using a120mm Schneider Macro Symmar HMlens. (This is an astonishing result, and will be reported on in full in my forthcoming P45 review. It needs to be said that if this was reported by almost anyone other than Bill I would question the conclusion. But since Bill is one of the most highly respected technical voices in the industry today it has to be taken seriously).

So, to answer the inevitable question –there is regrettably no one single answer. We’re talking about the very highest levels of performance, as well as fine gradations of results, individual perceptions, needs, and shooting techniques. There is no question in my mind, or that of any of the half dozen people that I know who have used or purchased a 39MP back (specifically the P45) that it is capable of producing results that challenge the best lenses and the best shooting techniques available. How to take that information and turn it into a purchase decision that’s meaningful to ones own needs is up to each individual. Fortunately, such backs are sold by VARs who provide their customers with units for testing and comparison. The only solution therefore is tosee for yourself.

_________________________________________________________________________

Update – Field-worthyness

Immediately upon publication of this article I heard from several people questioning the field-worthness of a system like this. My guess is that these questions are from people that have never shot with a large format or technical camera, and / or who have never used medium format digital.

I’ve been using myKodak DCS Pro BackandPhase One P25in the field for about two years. This use has ranged from the deserts of the American Southwest to Antarctica. I’ve never had an operational issue, in rain, blowing sand or snow, and neither from extreeme heat or extreeme cold.

As for the Linhof, it is simply a view camera, similar to those used by tens of thousands of landscape and nature photographers for the past hundred+ years. Other than tearing a bellow, (that’s what gaffer tape is for) what can break? No instant return mirror, no autodiaphram, no motor, no meter,no nothing. It’s simply a light-tight hunk of metal and plastic, and a pretty solid one at that.

As for weight and bulk, the complete system described above, including 4 lens and P45 back, fits in myThinktank AAbackpack, and weights 31 lbs, which incidentally is 3 pounds less than myContax 645system weighed. And since I’ve backpacked that system on five continents, I don’t see any reason why doing so with theLinhof / P45will be any different.

Large format lenses are, well, just lenses. Other than aCopalshutter, they contain no moving parts. Compared to a currentCanon EFlens with its motors, moving elements groups, circuit boards, image stabilizers, ROM chips and electronic contacts, such view camera lens are simplicity personified. I can swap a Copal shutter between lenses in the field in less than five minutes with a simple spanner. Anyone care to replace the shutter mechanism on their Canon or Nikon in the field with simple hand tools?

In fact I’d say that this system is likely as rugged for field use as any I’ve ever used. The sliding back makes it a bit bulky (and can catch the wind) but that’s all. And as far as operational convenience goes, it’s probably the fastest operating LF camera that I’ve ever used, and over the past 40 years I’ve shot with a variety of brands, includingLinhof,Sinar,Toyo, etc. (I was Sinar’s Canadian Product Manager for a number of years, and used both F and P models in the studio and field (and taught their use) for over a decade.

The biggest danger that I see is losing the expensiveKaptureGroup1-shot synchro cable. My solution there is to have a backup double-shot cable tucked in an inside pocket of my pack.

From the emails I’ve received it appears that a number of people are unaware that photographers by the thousands are out in inclement weather and inhospitable locations shooting with large format view cameras every day. Their gear ranges from 679, to 4X5, to 8X10" cameras, and even larger.The current issue of The Video Journalhas an interview with and shows me shooting in the Florida Everglades withClyde Butcher, who regards anything less than 5X7" film assmall format.

The only difference between what Clyde, and the thousands of large format photographers like him are doing, and what I am doing, is substituting a small self-contained digital back for a sheet film holder (actually many of them). And (oh yes) my camera is smaller and in many cases lighter than theirs.

Field-worthy?You betacha!

_________________________________________________________________________

One More Thing

There’s always one more thing, isn’t there?

There have also been several emails from people expressing their dismay that equipment such as this somehow gets in the way of, or is a substitute for creativity. My response –rubbish!

Photographers of all pursuits use the best equipment that they can for their specific task. Working primarily as a fine-art landscape photographer my goal is to immerse the viewer in the image I have captured in an attempt to have them see what I saw, and if possible, how I saw it. This type of photography demands the highest possible image quality, and is achieved by using the best quality tools that one has available.

Does using such tools reduce or somehow get in the way of ones creativity? I really think not. That’s like saying that a Formula One driver doesn’t need the best possible car, or that a world-class skier doesn’t need the best possible skis. Tools are what allow human beings to accomplish their desires, and my desire is to create images that best communicate what I see, be it with aFunkycamor aLinhof / P45.

_________________________________________________________________________

Feedback

As one might imagine, since it first appeared this article has engendered a great deal of commentary, on this site’s forum as well as a few others. It also generated quite a few emails, including the usual gripes and zingers but also several insightful observations by photographers who struggle with the same issues intheirwork.

Below is one such email; one that I feel summarizes well the dilemma that many photographers face.

Your article dealing with the many factors involved with your decision to purchase a new outfit, was the best review I’ve read. Virtually all photographers, serious amateur and professional, have to deal with these questions, which are both time consuming and expensive in todays marketplace. I recently tested the Phase One P25 & P45 backs on my Contax 645 system and compared the results with my 4×5 field camera. My primary camera for many years has been a Toyo 4x5Aii. I drum scanned the 4×5 transparency and printed all three images to 24×30. I do not have a printer that is larger. To my eye, there was no difference between the P25 & P45 prints. I think that both are comparable to the print from the 4×5 film camera, with only subjective differences due to lighting and lenses used. I have been told that at 30×40, I would be able to see a noticeable difference between the film and digital images. Having practiced fine art photography for 15 years, I continue to be amazed at what a continuum the learning curve is for those of us who work in this craft. Everything that I do seems to come with difficulty. Thanks, for a job well done.

March, 2006

You May Also Enjoy...

vj-partner-infor

Hi, We have now begun our partner program. This will allow you to earn USD $20 for each person that subscribes to theLuminous Landscape Video

Year in Review, Year Ahead Part 3 – Lenses and Printing

FacebookTweet We’ve seen a lot of innovation in lenses lately, and I’m looking forward to more this coming year. The full-frame mirrorless mounts are really