William James once said “A chain is no stronger than its weakest link”.

That statement applies to many things in life, including the area of ink jet printing.

I can remember back to the days of the original Iris printers, and I still marvel at how those devices set the stage for both digital fine art and photographic print making. But, unlike previous technologies such as Lithography (a fancy word for offset printing) or Serigraphy ( a fancy word for silk screening), early inkjet printing wasn’t immediately welcomed into the world of limited edition art. In fact it had to prove its legitimacy, and, one of the first proving grounds was the archival properties of its ink and media.

No one could contest the visual quality of an Iris print. The vibrant CMYK dye inks could produce a color gamut beyond that of an RGB monitor. But would it last? Sadly, the answer was no—at least when comparing to a photographic print. Depending on the paper you used, you could expect anywhere from 3 years to 20 years before fading could be visually detected. And while there were a few attempts at a more balanced inkset over the life of the Iris, the best estimated longevity it ever managed on archival paper was about 36 years—and that was with a severely restricted gamut compared to its more vibrant, less archival, original dye inks. In comparison, a very vibrant color negative printed on Fujicolor Crystal Archive paper would last around 40 years.

For those pioneering Iris printers, when it came to ligthfastness, the combination of both magenta and yellow inks were the weak link due to catalytic fading.

Fast forward to today. Inkjet printers have made amazing advances in both longevity and color gamut, but one key factor remains true. Yellow is now most often the ink that fades fastest and shows the most instability over time.

But… you wouldn’t know that based on industry-sponsored print longevity test results.. Perhaps this is to be expected when testing criteria developed for one set of processes (photography) is applied to a totally different set of processes (ink jet printing). In a limited sense the testing is valid. But, without taking into account the content of the images and the methods used to print them, is it complete?

“Our aim is to provide the answer to the question: ‘How long will this image last before noticeable fading and/or staining occur, and under what conditions?’” – Wilhelm Imaging Research, Inc.

As far as I know there are two laboratories routinely conducting accelerated light fast testing and publishing print longevity information on ink jet printers, inks, and media.

The most well known of course is Henry Wilhelm at Wilhelm Imaging Research (http://wilhelm-research.com). For years, Wilhelm has been the defacto standard when discussing longevity of photographic and inkjet prints. Neither the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) nor ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) currently provide an international standard for light fade testing of modern digital print media.

However a new set of tests, using a different methodology that employs the “I* Metric” (pronounced eye star) to measure color tonality and accuracy, have recently been undertaken byMark MCcormick-Goodhart of Aardenburg Imaging & Archives (http://www.aardenburg-imaging.com/) .* These tests have some important differences with those of the past, differences that I think make them a more complete and useful method of judging the longevity that inkjet prints are capable of achieving.

A little explanation. Light fastness testing methods developed for traditional photographs seek to measure how the photographic dyes are affected when subjected to the direct exposure of light. If these tests only look at a few specific pure values in the print, the test results can still give us a basic understanding of the fading process because all the colors in the photographic print are formed with just three dyes; cyan, magenta, and yellow. Because all three dyes are subject to fading independently of each other and because all three dyes must be used to form neutral colors in the image then this global fading perspective will paint a fairly clear picture of changes to overall color balance. And if there’s a dye that’s a weak link—and to one degree or another there is always a weak link—these tests still remain accurate since there’s little that can be done to change the use of the weak link colorant in the development process.

Now if we take that same test and apply it to inkjet prints we get a set of values that upon first inspection also appears to be accurate. Even given the fact that yellow is the weak link among the inks, this data looks as though it represents overall permanence of the ink and media accurately with yellow as the limiting factor.

But does it? Well, since with ink jet printing we know that yellow disproportionately affects the permanence of the print, we first have to ask: how much yellow was used to form the colors in the test sample? Or was the test only done on the pure colorant? What was the subject matter in the print if any? Was it pure color wedges of each ink? Was it perhaps a landscape image or a portrait image? And finally… what method was used to print the sample?

Perhaps you see where I’m heading with this. Because we have an ink set with one colorant that is the stumbling block when it comes to permanence, how much of that colorant is used in the sample can greatly determine the outcome of the test. A test print that uses no yellow ink will yield a much higher value than one that uses a lot of yellow. In practical terms this means that a print containing a large amount of skin tones will not have the same level of permanence as a print that contains no skin tones because yellow ink is typically used to reproduce those tones. Since images containing people account for over 80% of all consumer photos one would think color blends, especially skin tones, would be an important image area to test permanence, yet only the I* test method used by Aardenburg Imaging accounts for the effects of colorant blending in the final print.

Hence, there’s another huge, and very related, factor that comes into play when evaluating the overall lightfastness of inkjet prints: The ink set, and how it is utilized.

Specifically, let’s take a look at two ink sets from the same manufacturer: Epson’s Ultrachrome K3 inks and the Epson Ultrachrome HDR inks used on newer printers such as the Epson 4900, 7900 and 9900.

Ultrachrome K3 with vivid magneta and Ultrachrome HDR use identical inks except that HDR has the addition of both an Orange and Green ink. Is that important for longevity? Not if we look at permanence numbers from Wilhelm. Both ink sets and the earlier K3 ink set for a given media show ratings that are absolutely identical. On the surface that makes sense. Yellow is still the limiting factor in these Ultrachrome ink sets, after all, so the test scores should logically be the same, right? We don’t even need to run new tests for the newer ink sets -just copy the media scores from the earlier K3 tests and apply to the K3VM and HDR ink sets on the same media.

Not so fast

Just as the greatest print makers of the past achieved their results by experimenting with bath times and formulations, the same is true with ink jet printing. Process matters. Yet when we look at the commonly accepted permanence data, there is a recurring theme of something missing. Process. There is never a mention of how the samples were printed. By that I mean what software was used. Up until now, the important role that software can play in this discussion has been ignored. But, history shows that software can matter when it comes to making longer lasting prints.

It can matter quite a lot, in fact.

A little of that history: Around 10 years ago ColorByte Software released a Black and White printing system for Epson Ultrachrome inks as part of their ImagePrint software. By using only the black and gray inks, and trace amounts of other colors, there was finally a way to obtain a perfectly neutral and stable print using OEM inks. What made them so stable? Well, plainly stated, there was (and is) absolutely no yellow ink used. Even the Epson driver’s ABW mode, largely modeled after what ImagePrint does, still can’t get away from relying on yellow ink (as can easily be seen under a loupe). So when it comes to permanence for B/W prints one would have to guess that prints made with ImagePrint’s model would last longer and be more stable. That would stand to reason since they demonstrably contain not a drop of that infamous longevity killer, yellow. Sadly, though, it would have to be just that. A guess. The software used is not noted in the commonly accepted longevity tests.

Let’s fast forward back to color printing in the here and now, using the most modern inkset available. Can a print made with Epson Ultrachrome HDR inks out last one made with just Ultrachrome K3. If we only want to look at the data provided by Wilhelm one would think not.

But again—process matters.

And a process that reproduces color by using non-standard ink combinations can break through the status quo by significantly reducing the use of the weakest link ink.

ImagePrint makes extensive use of the HDR Orange and Green ink. In fact to whatever extent possible it is used in place of yellow for creating common skin tones. At the same time, ImagePrint also makes extensive use of the Green inks of the HDR set, allowing yellow to be reduced even more. This means that, just like with black and white printing, ImagePrintcanpositively affect the permanence and stability of the print through printing technology.

But what about other methods of printing, such as through the standard Epson driver? Don’t they also substitute orange and green inks for yellow wherever possible?

Yes, but not to the same extent. Gamut tests have consistently shown ImagePrint takes full advantage of the orange and green inks of the HDR set to increase the gamut of prints up to 15% over that of the Epson driver. That fact alone shows that software can improve upon what the printer is capable of.

But the increased fade resistance that the orange and green inks potentially offer hasn’t been tested. Until now.

For the first time someone has actually compared the light fastness of printing via the Epson driver and ImagePrint when using HDR inks. The results can be found here http://aardenburg-imaging.com/light-fade-test-results/

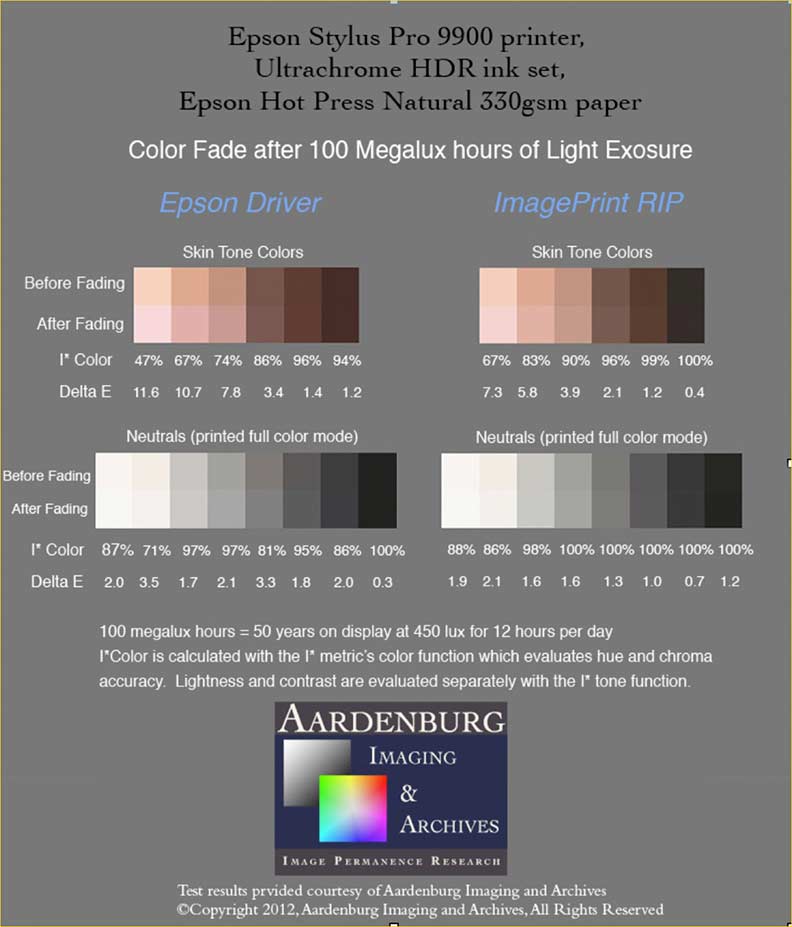

The findings are quite impressive, and a clear indication that advanced printing technology that utilizes the orange and green inks aggressively can significantly increase the stability and longevity of your prints. Here’s a sampling of some of those results:

From the Aardenburg Imaging Light Fade Test results Database–

Using the same batch of Epson Hot Press Natural paper:

ID#164

Printer: Epson Stylus Pro 9900

Inkset: Epson OEM UltraChrome HDR™

RIP: ImagePrint

Paper: Epson Hot Press Natural 330gsm

AaI&A Conservation Display rating =90-100+ Megalux hours

(i.e., sample still passing upper limit criterion at 100 megalux hours total light exposure).

Compare to:

ID# 166

Printer: Epson Stylus Stylus Pro 9900

Inkset: Epson OEM UltraChrome HDR™

Driver: Epson OEM

Paper: Epson Hot Press Natural 330gsm

AaI&A Conservation Display rating =53-89 Megalux hours.

Using the same batch of Epson Hot Press Bright White paper:

ID# 168

Printer: Epson Stylus Pro 9900

Inkset: Epson OEM UltraChrome HDR™

RIP: ImagePrint

Paper:Epson Hot Press Bright White 330gsm

AaI&A Conservation Display rating =still passing both lower and upper criteria at 100 megalux hours.

Compare to:

ID#170

Printer: Epson Stylus Pro 9900

Inkset: Epson OEM UltraChrome HDR™

Driver : Epson OEM

Paper: Epson Hot Press Bright White 330gsm

AaI&A Conservation Display rating =69-97 Megalux hours.

Note specifically in both sets of tests that the lower Conservation Display limit (CDR) increases by over 30% for the Image print samples compared to the same media printed via the Epson OEM driver. The Lower CDR is the lead number in the Aardenburg test score and is expressed in megalux hours of exposure. It is a direct measure of how much light exposure the worst 10% of the colors in the print sample can tolerate and still remain in excellent condition with little or no noticeable fade. For Epson Ultrachrome inks, those colors are typically the light skin tone colors which must be formed with liberal amounts of magenta and yellow inks or by careful substitution of yellow and to a lesser extent magenta with the HDR orange inks. Because the ImagePrint RIP utilizes a larger amount of the more lightfast orange ink than the Epson driver, the overall light fastness of prints containing important skin tone colors is greatly enhanced, and this favorable outcome is detected in the Aardenburg light fade test method.

In closing, it should be noted that longevity testing is complex, time-consuming and expensive and by highlighting the Aardenburg Imaging results I certainly don’t want to belittle the accomplishments of Wilhelm Imaging Research, Inc. I strongly believe it is a good idea to familiarize yourself with both companies’ testing methods and draw your own conclusions. It should be noted that Wilhelm Research is also a proponent and co-develper of the I* metric, but only Aardenburg Imaging has thus far implemented it in a modern light fade testing protocol for digital printing systems. Acceptance of new standards takes time, and it is unclear whether the ISO or ASTM will adopt a light fade testing method as comprehensive as the Aardenburg Imaging protocol any time soon.

Still, when longevity of prints is of concern, the more complete story offered by these results could well be a deciding factor in which printer to purchase. Especially considering how often I have heard that there is little difference between an Epson ‘890 series printer and a ‘900 series printer (other than the price). These results imply quite a different story. They show that there can be significant and unexpected differences–at least when the printer is combined with advanced software. One might even say that if the software driving your printer doesn’t utilize the full ink set it to its maximum potential then maybe using the wrong printing software is another weak link in the chain.

September, 2012

Full Disclosure:

John Pannozzo is the president of ColorByte Software and therefore has intimate knowledge of the workings of ImagePrint but not of other 3 rd party software. For this reason no other 3 rd party software was mentioned in this article and to my knowledge none have been tested by an independent party for permanence ratings. ColorByte did not help or participate in any way prior to or during any testing at Aardenburg Imaging and was only made aware of the findings after the fact.

Bio:

John Pannozzo has worked in the graphics industry since 1988. First as a system designer for broadcast video and animation. In 1992 ColorByte Software was born out of the need to print large scale computer generated graphic files to an Iris printer. The development of core technologies centered around color separation also paved the way for software development in the area of drum scanning. The last 10 years have been dedicated to the development of ImagePrint and the technology to enhance the printing capabilities of modern ink jet printers used in the production of photography and fine art print making.

*I recommend you read an overview of the Aardenburg display rating system. You can find that document here http://www.aardenburg-imaging.com/documents.html (It is the third file down.) At the bottom of the document is a little about the author and you can start to piece together not only his background and expertise in the field but also how his testing methods differ from that of Wilhelm and the significance of those differences.

You May Also Enjoy...

Super-Vid

Super Telephoto Technique From Issue #4 Click on the image below to play a briefQuicktimevideo clip from Issue #4 of theVideo Journal. Remember, theVideo